Por qué importan los términos “segunda generación” y “tercera generación” para las comunidades latinas de Filadelfia

Garett Fadeley

Filadelfia nunca ha sido tan diversa, y las familias latinas desempeñan un papel central en esa transformación. Para 2024, más del 16 % de la población de la ciudad se identifica como latina. Si bien muchas personas han llegado recientemente desde Puerto Rico, República Dominicana y México, la mayoría de los latinos en Filadelfia hoy nacieron aquí. Representan una proporción creciente de residentes de segunda y tercera generación.

Al mismo tiempo, continúan llegando nuevos inmigrantes desde Asia, el Caribe y América Latina. Sus hijos nacidos en Estados Unidos —especialmente dentro de familias latinas— están ayudando a redefinir qué significa pertenecer en Filadelfia.

«Creo que es importante asociarse con algún tipo de identidad, especialmente si estás confundida sobre tu lugar», dijo Anisa Cabrera, estadounidense de segunda generación con raíces mexicanas.

Sin embargo, las conversaciones públicas suelen enfocarse en los inmigrantes, no en sus hijos o nietos. Y eso es un problema. Los latinos de segunda y tercera generación no solo heredan cultura: están definiendo activamente la identidad, la cultura y la vida cívica de la ciudad.

¿Quiénes cuentan como segunda o tercera generación?

STEPHEN KNIGHT

La Oficina del Censo de EE. UU. define como personas de segunda generación a quienes nacen en el país y tienen al menos un padre inmigrante. La tercera generación (o superior) incluye a quienes, junto a sus padres, también nacieron en Estados Unidos, pero tienen abuelos inmigrantes (u otros antepasados que migraron).

Estos términos ayudan a entender cómo evolucionan el idioma, la identidad y la cultura a lo largo del tiempo, especialmente en ciudades como Filadelfia, donde muchas familias habitan entre múltiples espacios culturales. Los latinos de segunda y tercera generación suelen actuar como puentes entre esos mundos, traduciendo, adaptando y transmitiendo tradiciones.

Idioma, identidad y continuidad cultural

El idioma suele ser el indicador más claro del cambio generacional. Muchos latinos de segunda generación crecen siendo bilingües, hablando español en casa e inglés en la escuela. Pero no siempre es así.

«He notado que muchas veces los puertorriqueños no le enseñan el idioma a sus hijos», comentó Arianna Alfaro, puertorriqueña de segunda generación. «No sé por qué, porque el español fue la primera lengua de mis padres, y aún así nunca me la enseñaron».

Con el tiempo, Alfaro aprendió español en la escuela y la comunidad, pero no en casa.

Para la tercera generación, el inglés suele predominar. Aun así, el español conserva un valor emocional y cultural importante. Dos hermanas colombo-mexicanas del noreste de Filadelfia reflejan este contraste generacional: la mayor aprendió español primero y aún lo habla con fluidez; la menor aprendió inglés primero y hoy casi no habla español.

«Ahora que soy adulta, cuando hablo con mi mamá en español», dijo Roxann Lara, la hermana menor, «me gustaría haber aprendido el idioma de niña para poder comunicarme sin barreras. Por eso inscribí a mis hijos en un programa de inmersión en español en una escuela pública».

Este patrón no es raro cuando hay migración generacional.

«Los hijos mayores generalmente hablan mejor español porque sus padres solo hablaban español cuando nacieron», explicó Jeanpaul Gonzalez, colombiano de segunda generación. «Ya cuando nacen los hermanos menores, los mayores ya hablan inglés y los padres también empiezan a usarlo. La conexión con el español se va perdiendo».

También hay presiones en el entorno laboral.

En el trabajo, se espera que yo sepa español para traducir», dijo Alfaro. «Eso lo hace más difícil porque me hace sentir que he fallado como latina por no saber hablar el idioma. Es desalentador que se espere eso de mí y no poder cumplirlo».

Según el Pew Research Center, el español sigue siendo el idioma no inglés más hablado en los hogares de Filadelfia, con unas 160.000 personas que lo utilizan. A nivel nacional, el 61 % de los inmigrantes latinos habla español en casa, pero ese porcentaje baja al 6 % entre los de segunda generación y prácticamente desaparece en la tercera. Aun así, el 88 % cree que es importante transmitir el idioma.

«Es súper importante pasar conocimientos básicos y el idioma», reiteró Cabrera. «Para mí, como hija de padre mexicano que creció siendo ‘no sabo kid’, es frustrante».

Falta de datos en Filadelfia

A pesar del creciente interés en el bilingüismo y la identidad, los datos locales siguen sin contar toda la historia. Las encuestas más importantes registran el lugar de nacimiento, pero rara vez el de los padres o abuelos, lo que hace casi imposible identificar o entender a la población latina de tercera generación.

Muchos programas siguen diseñados pensando en inmigrantes recientes, pero eso no ayuda a un adolescente de tercera generación que lucha con la pérdida de identidad, ni a un padre de segunda generación que intenta reconectarse con el español a través de sus hijos.

¿Por qué importa ahora?

Con demasiada frecuencia, la comunidad latina es tratada como un grupo homogéneo, cuando la realidad es mucho más compleja.

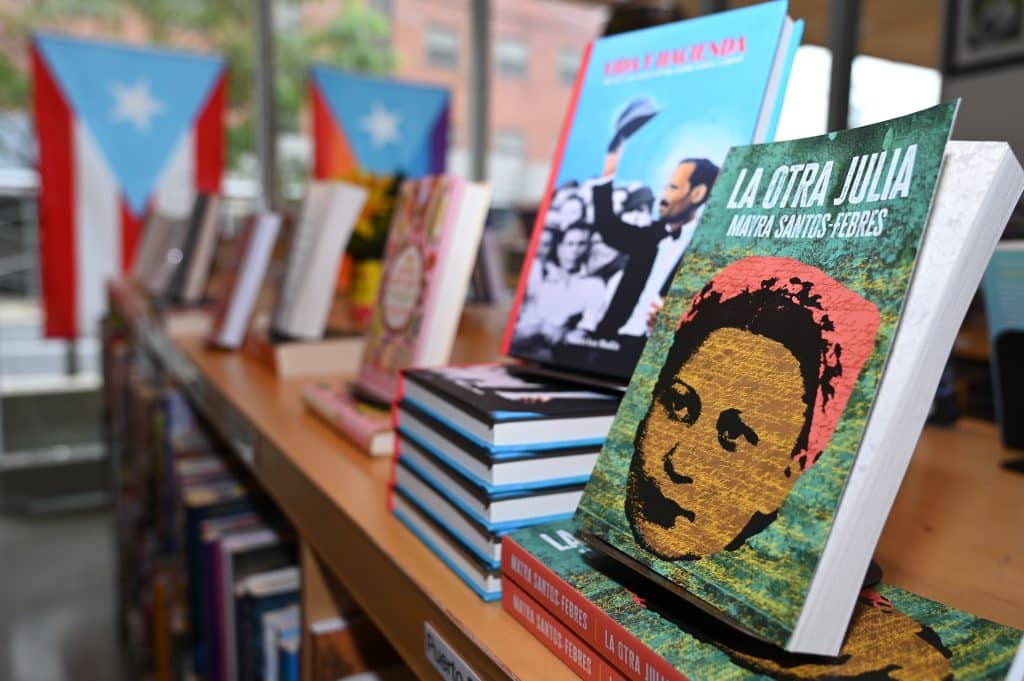

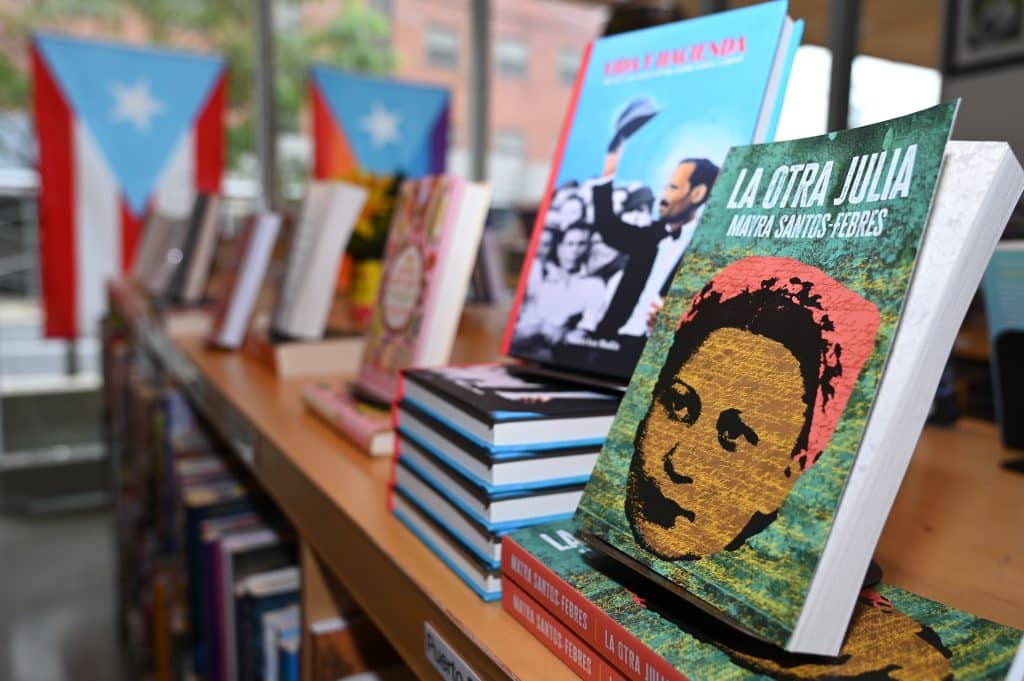

Por eso, contar nuestras historias y preservar la cultura es tan importante. Organizaciones como Taller Puertorriqueño, Concilio y Pequeños Pasos hacen ese trabajo a través del arte, programas de primera infancia, historias orales y eventos culturales. Ayudan a que los latinos multigeneracionales se sientan conectados con sus raíces y su lugar en la ciudad.

Qué sigue en la serie

Este artículo es el primero de una serie sobre los latinos de segunda y tercera generación en Filadelfia. En la próxima entrega: cómo están dando forma a la ciudad a través de la comida, la música, la vida escolar y sus experiencias cotidianas.

Why the Terms “Second-Generation” and “Third-Generation” Matter for Philadelphia’s Latine Communities

By Garett Fadeley

Philadelphia has never been more diverse, and Latine families play a central role in that transformation. As of 2024, over 16% of the city’s population identifies as Latine. While many are recent arrivals from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico, most Latines in Philadelphia today were born here. They now represent a growing share of the city’s second- and third-generation residents.

At the same time, new immigrants continue to arrive from Asia, the Caribbean, and Latin America. Their U.S.-born children, especially within Latine families, are helping reshape what it means to belong in Philadelphia.

“I think it’s important to associate with some type of identity, especially if you’re confused about where you fall,” said second-generation Mexican American Anisa Cabrera.

Yet public conversations often focus on immigrants themselves, not their children or grandchildren. That is a problem. Second- and third-generation Latines are not just inheriting culture; they are actively defining the city’s identity, culture, and civic life.

Who Counts as Second- or Third-Generation?

The U.S. Census Bureau defines second-generation individuals as U.S.-born people with at least one immigrant parent. Third-generation or higher means both the individual and their parents were born in the U.S., with immigration in the family history going back to grandparents or earlier.

STEPHEN KNIGHT

The terms help explain how language, identity, and culture shift over time, especially in a city like Philadelphia, where many families live between multiple cultural spaces. Second- and third-generation Latines often serve as bridges between those spaces, translating, adapting, and passing traditions forward.

Language, Identity, and Cultural Continuity

Language is often the clearest indicator of generational change. Many second-generation Latines grow up bilingual, speaking Spanish at home and English in school. But that’s not always the case.

“I noticed a lot of the time Puerto Ricans don’t transfer the language to their kids,” Arianna Alfaro, a second-generation Puerto Rican, said. “I can’t say why, because both my parents’ first language was Spanish, and I’m just confused why I wasn’t taught it.”

She eventually learned Spanish through school and community, but not at home.

By the third generation, English usually dominates. Still, Spanish often holds emotional and cultural significance. Two Colombian-Mexican second-generation sisters from Northeast Philly reflect this generational contrast. The older sister learned Spanish first and still speaks it fluently. The younger one learned English first and now speaks little Spanish.

“Now as an adult, when I speak with my mother in Spanish,” Roxann Lara, the younger sister, said. “I wish I had learned the language as a child so I could communicate without a barrier. That’s part of why I enrolled my sons in a Spanish immersion program at a public school.”

This is not an uncommon occurrence as generations migrate.

“First-born kids usually speak better Spanish because their parents mostly spoke Spanish when they were born,” second-generation Colombian Jeanpaul Gonzalez said . “By the time younger siblings come along, the older ones already speak English, and parents start to lean on that too. The connection to Spanish fades.”

There’s also pressure in the workplace.

“In work settings, I’m expected to know Spanish to translate,” Alfaro said. “That makes things difficult because it makes me feel like a failure as a Latina not being able to speak Spanish. “It’s disheartening to be expected to translate and not be able to.”

According to Pew, Spanish remains the most common non-English language spoken at home in Philadelphia, with around 160,000 speakers. Nationally, 61% of immigrant Latines speak Spanish at home, but that drops to 6% among second-generation Latines and nearly zero by the third. Still, 88% believe it’s important to pass on the language.

“It’s super important to pass on basic knowledge and the language,” Cabrera reiterated. “For me, as a ‘no sabo’ kid with a Mexican father, it’s frustrating.”

The Data Gap in Philly

Despite growing attention to bilingualism and identity, local data still fails to reflect the full story. Major surveys track birthplace, but rarely include parent or grandparent origin, making it nearly impossible to identify or understand third-generation Latines.

Many programs are still designed with recent immigrants in mind, but that doesn’t help a third-generation teen wrestling with identity loss or a second-generation parent trying to reconnect with Spanish through their children.

Why It Matters Now

Too often, the Latine community is treated like a monolith when the reality is far more layered.

That’s why community storytelling and cultural preservation matter. Organizations like Taller Puertorriqueño, Concilio, and Pequeños Pasos are doing that work through arts, early childhood programs, oral histories, and cultural events. They help multigenerational Latines feel connected to their stories and their place in the city.

What’s Next in the Series

This article is the first in a series on second- and third-generation Latines in Philadelphia. Next: how they’re shaping the city through food, music, school life, and everyday experiences.